The limits of counter-culture

In the last installment of my narrative, I described how I fell into the orbit of the French Anarchist Federation and turned my back on the counter-cultural anarchist-influenced world that I had been moving within. This might seem like a relatively minor development from an ideological point of view – a migration between two different branches of the tiny anarchist niche. However, in terms of culture, a major chasm separated them. The gap represents a major and persistent cleavage in the anarchist world, that between what is known as "lifestylism" and ‘class struggle’ anarchism. This is a modern twist of an age-old divide between cultural and political conceptions of leftist change.

Historical Roots

Alternative, counter-cultural worlds have always existed alongside and in parallel with the world of leftist politics. The very earliest modern socialists, such as Robert Owen and Henri de Saint-Simon, were considered to be ‘utopian’ by Marx - by which he meant that their theories of social change were based on wishful thinking. One important feature that many of these early socialists shared was a strategy of establishing model communities as blueprints for a future society and hoping to spread outwards from these seeds through cultural contagion and the persuasive prestige of a good example.

From Marx’s time onwards, the mainstream of socialist thought has rejected this strategy. Political socialists seek to advance towards a socialist world through participation in the conflicts that the capitalist economic system generates internally. Their strategy revolves around intervening in the economic struggle between the providers of labour and the owners of capital rather than establishing autonomous communities as islands of alternative values within the capitalist system. Serious socialists have, at times, embraced cooperatives and other alternative economic forms, but the establishment of alternative communities has generally been beyond the pale.

This has, of course, not stopped people from trying. Attempts at putting socialist, egalitarian, ideals into practice through the establishment of alternative communities have persisted despite the lack of a strong theoretical basis. Many people tend to look at the world through moral rather than systems-based lenses. When they are attracted to the left, it is based upon moral objections to the exploitative and unequal nature of the capitalist economy. The most immediate question that concerns them is “how do I live a good life in this exploitative world?” The answer provided by the political socialists – become a foot-soldier in the industrial army of the proletariat and help to build towards a revolution which will arrive whenever objective conditions allow – is unpalatable to many who are, understandably, less than enthused by the prospect of waiting for an event that may not come to pass within their lifetime.

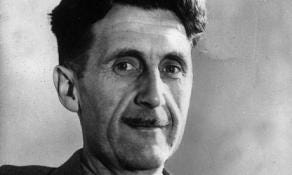

every fruit-juice drinker, nudist, sandal-wearer, sex-maniac, Quaker, ‘Nature Cure’ quack, pacifist and feminist in England.

George Orwell, The Road to Wigan Pier, 1937

The impulse to create alternative communities is particularly strong in those non-conformists who feel themselves to be marginalised, excluded or repressed by mainstream cultural norms. Communes provide such people with spaces in which they can define an alternative culture which embraces their unconventional ways, while also allowing them to live moral lives, untainted by the grubby exploitation and cruelty of the world around them. In many ways, non-conformist socialist and religious autonomous communities resemble one another and blend into one another at the edges - communities that attempt to institute the kingdom of God on earth tend to end up looking a lot like a commune. In both cases, the impulse is the same - to live a moral, if unconventional, life in the here and now rather than waiting endlessly for rapture or revolution.

The attraction of socialism to culturally unconventional people has frequently been bemoaned by political socialists who have seen the alternative communities as detracting from their message’s appeal to the broad cultural mainstream. George Orwell, for example, decried how the Socialist movement of the 1930s drew, “with magnetic force every fruit-juice drinker, nudist, sandal-wearer, sex-maniac, Quaker, ‘Nature Cure’ quack, pacifist and feminist in England.” Although the list of eccentricities has changed with the times - fruit juice drinking has been firmly incorporated into the cultural mainstream - similar laments can be heard from modern political socialists when they encounter modern utopian, non-conformist communities full of vegans and spiritualists.

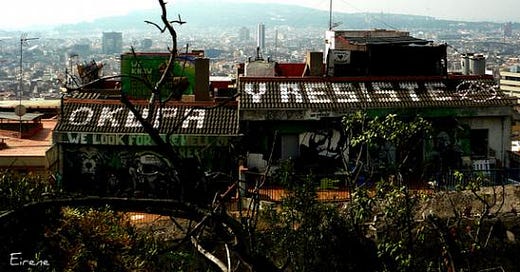

Today's anarchist-influenced counter culture is a modern twist on the alternative utopian communities that have accompanied the socialist movement from the start. This counter-culture emerged in the industrialised countries, from the late 1960s onwards. At its core is the idea of establishing alternative social and political spaces, often housed in squatted property, in which culturally-autonomous egalitarian communities could flourish. The character of these squats and social centres changes from country to country and centre to centre, but they have enough in common that they can be considered to constitute a political-cultural movement.

This movement started in the cultural liberalisation protest movement of the 1960s, then spread and expanded through the 1970's and 1980s, particularly in the core European social democracies of France, Germany, the Netherlands, Italy and Spain. The political ideas are somewhat influenced by anarchism: horizontal, non-hierarchical, participatory and socially-permissive forms of internal organisation and culture are widely-shared values, but also by autonomist Marxism - a branch of leftist though which focuses on the need for the working class to establish its own culture, independently of the culture offered by the hegemonic state and market. However, these political ideals are mostly vague, implicit and diffuse. Many of those who are drawn to this counter culture are people who feel most excluded and marginalised by mainstream culture. They rarely have a worked-out strategy for broad political change and, like the majority of the population, are little interested in abstract political theory.

Lifestylism vs Class Struggle

This anarchist-influenced counter-cultural movement has, naturally, attracted its fair share of criticism from political anarchists. In this debate, the political theories that underlie the counter culture are denounced as 'lifestylism'. Lifestylism is the idea that people can profoundly change the way that the world works through lifestyle choices. Seen through this prism, counter-cultural community building is merely an extreme form of ethical consumerism - not qualitatively different than buying 'fair trade' coffee or local vegetables.

A number of writers and publications have taken up the gauntlet on the side of the lifestylists. The best known of them include Bob Black, Hakim Bey, John Zerzan, Raoul Vaneigem, the CrimethInc Collective, Fifth Estate Magazine and Anarchy: A Journal of Desire Armed. Few of them would accept the lifestylist label, which is almost exclusively used by their critics. It would be fairer to say that their common feature is a focus on building autonomous communities. They describe themselves using a variety of compound ‘isms’, which draw equally from the lexicons of politics and post-modernism. Let me present the “post-leftist” anarchists and their off-shoot, the “post-anarchist” anarchists. These writers typically defend the transformative potential of a range of practices that are associated with the counter-culture, which could include any subset of squatting, refusing wage work, breaking the law, becoming vegan, dumpster-diving for food, transforming inter-gender relations, or even just holding free parties.

The battle between the anarchist theorists of the far-left and the idiosyncratic theorists who they call lifestylists, has produced a steady stream of polemical publications over the years. Highlights include Murray Bookchin’s Social Anarchism or Lifestyle Anarchism: An Unbridgeable Chasm, on one side, and CrimethInc’s Your Politics Are Boring As Fuck on the other. These theoretical arguments suffer from the fact that both sides take the lifestylist writers seriously as the theoretical expression of the counter-culture. Their anarchic rhetoric may have a certain resonance, but their theories are so bad as to be silly. They struggle to make even the most basic coherent logical arguments and they advocate extraordinarily silly ideas which makes one suspect that it's all some sort of attention-seeking prank. John Zerzan's opposition to symbolic thought, on the grounds that it mediates between us and our immediate, lived existence wins the gold prize, but he has many keen competitors. In any case, these debates are mostly academic - very few people adhere to the counter-culture due to being theoretically convinced of the efficacy of the general strategy that it embodies. Nevertheless, despite the extreme weakness of the case put forward by its theorists, the general approach embodied by the counter-culture does represent a logically coherent strategy. It can be summarised as follows:

Communities that operate against the cultural mainstream, outside the laws of the state and the market economy, can serve as poles of attraction for individuals who are discontent with the current repressive shape of society. Simultaneously, they can be experimental testing grounds where the shape of a potential new, post-capitalist order can be devised. As people establish more autonomous communities, with alternative social and economic systems, the capitalist economy will become increasingly hollow. As the new system grows, the old system will fade. By the time the majority of the population has defected and the capitalist system has collapsed, a functioning new order will be waiting in the wings to take its place.

When I made my personal jump from the counter-cultural world to the far-left, I was aware of the theoretical debates that were raging between lifestylists and class-struggle anarchists. Experience and observation were, however, much more significant in convincing me that the sort of counter-cultural experiments that I saw were not capable of spreading or scaling in any serious way. The problem with the strategy was not something that could be deduced from first principles. The problem was that the strategy didn't work in practice. The counter cultural communities that I saw shared a broad set of problems which effectively prevented them from scaling. I have since seen these same problems manifesting themselves, again and again, over many years. Before turning my back on this world in my narrative, I will describe the core problems that limit the strategy's potential for successfully inducing social change.

Hostility to Moralism

As communities largely populated by people who feel marginalised, excluded and repressed by mainstream culture, a core feature of counter-cultural communities is a broad permissiveness towards alternative lifestyles and a strong hostility to conventional moralism and moralists. Those who join the community have previously been immersed in mainstream culture and have internalised some of the cultural norms that are considered repressive by the community – attitudes and behaviours deemed to be sexist, racist, threatening or morally judgmental. This means that vigilance is required to ensure the suppression of the judgmental instincts produced by the internalised residues of conventional morality. For example, while mainstream culture tends to generally look down on women who are sexually promiscuous, in the anarchist influenced counter-culture, any echoes of such attitudes are decried as ‘slut-shaming’. The problem, however, is that moralism serves an important function in group cohesion and it is difficult to replace.

One of the core debates in human evolutionary sciences over the last few decades has concerned what is known as ultra-sociality. Humans can be observed to act cooperatively across large groups, even sacrificing their own interests in favour of broader group interests. However, from a ‘selfish-gene’ point of view, this behaviour makes no sense. If one considers the gene as the only vector of natural selection, self-sacrifice only makes sense within a closely related kin group. When dealing with a broad social group, self-sacrificial strategies will be out-competed by selfish ones and the genes which encode selfishness will come to predominate. Hence selfish-gene theorists have tended to deny the existence of genuine ultra-sociality. Where the evidence for it is overwhelming, they claim that the individuals in question have been deceived, as evolution could not select for such behaviour.

However, in the last couple of decades, the pendulum has slowly swung against the selfish gene theorists and back towards what used to be called group selection and is now known as multi-level selection theory. According to this point of view, natural selection happens at many levels – from the individual, up to the family group, kinship group, village, town, region and nation. At the higher levels, culture, rather than genetics, is the vector of evolutionary change. Cultural practices which bestow greater competitive advantages on the group will tend to proliferate over time. Groups with a strong capacity for collective action can out-compete – particularly in warfare – more individualist groups, even when they are individually out-matched.

But this does not, by itself, solve the problem of how a group develops the capacity for ultra-sociality. Simple game theoretic experiments show clearly that, within groups, purely cooperative strategies will be out-competed by selfish infiltrators. The most plausible and sound hypothesis that addresses this problem is the theory that one of the key adaptations which individuals developed, to allow them to cooperate over very large groups, was the moralist strategy: “cooperate when enough members in the group are also cooperating, and punish those who do not cooperate.” Exactly how the strategy might have evolved is not important, what is important is the role that moralists play in group cohesion. They punish people who violate social norms, even when it comes at a cost to themselves. This may not be pretty, but it does help group cohesion by discouraging anti-social behaviours. Simple game-theoretic experiments show that a cooperative group with enough moralists can be resilient against selfish strategies.

The advantage of moralism as a means of enforcing social norms is that it is relatively instinctive – moralists are driven by the emotional satisfaction of punishing norm-breakers – and acts diffusely through a wide range of sub-conscious and instinctive social signals – disapproving looks, tut-tutting, moralising gossip and so on. This moralistic culture serves the function of reinforcing pro-social behaviours within the group, as well as helping to identify and isolate anti-social infiltrators. The second function is particularly difficult for a highly cooperative community to dispense with as the permissiveness of such communities makes them attractive to anti-social free-loaders and predators.

Alternative Branch of the Social Services

Within the counter-culture there is a strong sympathy for those who are perceived to be victims of capitalist society – the homeless, mentally ill, alcoholics and drug addicts, for example. There is also a strong aversion to excluding people from the community on the basis of their misfortune. This translates into a culture that is unusually tolerant of disruptive behaviour. Counter-cultural spaces can sometimes resemble alternative branches of the social services; places where the casualties of endemic social problems are taken in, and their socially disruptive behaviour contained.

This factor compounds the problems caused by the lack of clear social norms and moralists to enforce them. Together they ensure that counter cultural communities face a constant internal struggle against parasites and anti-social and disruptive behaviour. Sexual predators, violent and unpredictable addicts and chaotic mental illness sufferers and simple cynical free-loaders are naturally attracted to such permissive environments. Without well-understood norms for moralists to police, the community lacks diffuse cultural defences against disruption and must fall back on weaker and more labour intensive mechanisms like meetings, explicit codes of conduct and safe-space policies.

Attempting to deal with such matters takes up a considerable proportion of the organising resources of many counter-cultural communities. A single anti-social member has the potential to seriously degrade the community's fabric, yet dealing with such a matter normally requires a laborious process of discussions, work-shops, agreements and meetings whose success ultimately requires the troublesome individual to genuinely engage in the process. Where a troublesome individual is sufficiently cynical and stubborn, they can remain within the community, poisoning its atmosphere and sapping its strength, for years on end. The overall impact is that, far from being agile environments in which social experiments can be pursued, such communities are often incapable of solving the most obvious internal problems such as the unwanted presence of anti-social and cynical parasites.

Organisational Structures

Another major problem faced by counter-cultural communities is that they almost always depend on a relatively small core of highly-committed organisers. This happens, despite the stated open and non-hierarchical nature of such communities, simply because most people are not sufficiently committed to the idea of the community to devote all that much time and energy to sustaining it. Most people involved tend to be sympathetic to the basic philosophy and values of the community, but only a few are committed enough to devote a large proportion of their time to the tedious, minutiae which sustain it. Core community organisers tend to be secular saints. They are normally unusually pleasant individuals: idealistic and unreservedly cooperative and optimistic. They have to be to devote large chunks of their lives to doing the dull, often thankless organising work required to sustain an alternative community in frequently chaotic situations. Such people are in short supply.

Community organisers often make great efforts to ensure that users of their spaces can have a say in the decisions that affect them. In practice, however, such communities rarely stray too far from a model of a large number of consumers and a small team of organisers, simply due to variations in interest, idealism and commitment. The anarchist ideological opposition to hierarchy and the counter-cultural suspicion of formal structures make this a difficult problem to deal with. General community meetings are the most common decision making structure and often the only one. Yet many community members attend organising meetings irregularly or not at all, or worse still only when they are incensed by some perceived failure of the community towards themselves. Tasks assigned to non-core members are fulfilled with dependable irregularity. The crucial tasks fall back on the most committed, core organisers, but the openness of the structures means that meetings are often dominated by issues that are randomly injected into the agenda by whoever happens to attend. Given the ideological opposition to adopting structures which reflect functional divisions, over time such structures tend to lapse under the weight of dysfunction and decisions come to be made informally between the community’s core group – a ‘tyranny of structurelessness’ evolves.

The organisational structures employed within counter-cultural communities are rarely attractive models of how a future society could work - but when it comes to broader organisation, beyond the individual communities, the situation is worse. So much time and effort is invested in the intractable internal problems, that little time or energy remains for building broader structures that bring the counter-culture together in a focused way. There are, of course, numerous informal links between squats, social centres and the communities who build them. There have been occasional alliances, but these have been mostly short-lived and loose, based around specific protests or mobilisations. Enormous quantities of work have been poured into almost 5 decades of counter-cultural experimentation without leaving any meaningful institutional permanence. This means that, all too often, when a particular counter-cultural space closes down, it leaves little behind it - the community disperses leaving nothing but a folk-legend for the next generation of counter-cultural youth.

Hostility to mainstream culture

Although counter-cultural communities are typically very permissive, there is one notable exception. Adherence to the community is signalled through participation in its cultural world rather than any formal membership. In order for an alternative culture to survive in the midst of an overwhelmingly powerful mainstream culture, it is necessary to maintain a clear barrier between the two. An individual who wishes to become part of the community, and the broader counter-culture around it, must adopt a significant chunk of its cultural norms, aesthetics, sexual mores and so on, before they have put sufficient distance between themselves and external, repressive, society in order to be considered to belong to the counter-culture.

Although such communities reject conventional moralism, if they remain in existence over any period of time, they come to develop their own shared social norms and their own moralism to enforce those norms. The alternative norms which the community develops could include veganism, punk, polyamory, arcane language or internal group-communication practices using hand-signals, or any combination of unconventional, sub-cultural practices. These shared norms will naturally be seen as morally superior to those of mainstream society around them and moralistic mechanisms will emerge to enforce these norms simply because enforcing them through formal mechanisms is far too energy-sapping.

This sub-cultural moralism further increases the distance between the community and the general population in two ways. Firstly, community members can easily see themselves as being morally superior to the general population, and consequently look down upon them. Those who work for a wage in corporate jobs, or listen to commercial pop music, are sometimes considered as soulless drudges, unthinking foot-soldiers of the capitalist order, mere sheeple. This cultural hostility increases the difficulty of defecting from the mainstream to join the community.

Secondly, in my experience at least, alternative communities with social norms that one does not understand are very weird places indeed. "A lavishly bearded man in a skirt is standing over me, playing the banjo and staring at me. Nobody appears to be think that this behaviour is worthy of their attention - it must be normal behaviour here. I had better pretend that I'm totally comfortable with this. Right we are so." It’s especially weird when one attracts disapproving looks for breaching social norms that one is not aware of. New members of the community may have to go through substantial periods of negative moral feedback until they have learned enough to follow community norms.

Due to their roots in the new left politics of the 1960s and the fact that many of their adherents are attracted to these communities by the personal experience of feeling excluded by mainstream society, the politics of identity have a central position in the counter culture. They are environments where usage of politically correct language is widespread and those who offend group norms will attract forceful disapproval until they amend their ways. This, once again, increases the cultural distance between the counter-culture and the world around it. Not only do new adherents have to become comfortable with weirdness, but they have to learn a new lexicon in order not to be seen as sexist, racist or homophobic.

Relationship to Social Democracy

The final major problem faced by counter-cultural communities is their relationship with the social democratic structures of the societies within which they exist. On the most basic level, the relationship is parasitic – squats and alternative social spaces often depend for their survival upon resources and legislation which has been put in place by leftist administrations. It is much easier to establish and maintain a squat in a city with strong tenants’ rights and protections against eviction than in a city without them. It is rare that such communities reach such size that they could not be easily suppressed, evicted and shut down by the state. Their survival depends, to a considerable extent, on the tolerance of the state and society around them. This is borne out by any analysis of where and when political squats and counter-cultural spaces have flourished.

On the other hand, the provision of public services by modern democratic states also has the effect of removing the scope for alternative communities to expand among the population. The primary means by which such communities attempt to spread their values is through community outreach efforts which make their spaces available to the broader community in which they exist. For example, squats often make their buildings available to their neighbours for meetings, child-minding, educational classes or cultural events. The big problem is that they compete with existing organisations – public health and education systems for example, that are vastly better resourced and are less culturally alien to the population. The widespread development of such services through the welfare state has thus substantially reduced alternative communities’ ability to gain influence in the communities around them.

Furthermore, the era of the welfare state saw a very significant increase in the quality of life of large segments of the population in the industrialised countries. Joining an alternative community can mean sacrificing some of this. Participation in the cultural life of an alternative community is time consuming. It may require sacrificing security of tenancy, well-furnished heated housing, access to state services and even income from a wage. Hence community membership is dominated by those with least to lose and least responsibilities. Their membership is hence dominated by young people, without dependents and with little need for the safety net provided by the welfare state.

Where alternative communities persist for long periods of time, it is common for them to regularise their status in order to reduce the insecurity of their occupancy. For example, Berlin was a European centre of squatting in the 1980s and 1990s. Today, as the social and political climate has become increasingly more hostile, many of the established squatters have thrown in the towel and accepted leases and property titles which have regularised their statuses. It is hard to live without any security of tenure for a long period of time and, once the initial wave of enthusiasm and idealism has dissipated, the temptation for inhabitants and organisers to move their existence onto a more secure basis is hard to resist.

Conclusions

However, my observations and experiences have convinced me, overwhelmingly, that they do not work as a political strategy. The counter-cultural values and norms do not tend to spread, nor do the communities serve as useful experimental laboratories for a future social order. Their rejection of moralism and radical openness means that they spend a large part of their energy trying to shore up group cohesion and offset the negative effects of parasites while trying to deal with the broader social problems that society dumps on their always-open doors. Their organising structures are normally limited to specific communities, are frequently chaotic and often devolve to an informal core group. This does not provide a useful, scalable or desirable model of an alternative social order.

This has been a political analysis of the strategy of building autonomous communities and the counter-cultures that sustain them. It is not, in any way, a moral or cultural judgement on this sub-culture. On a personal level, I'm comfortable with considerable degrees of weirdness, I like bohemian cultural spaces and I normally enjoy visiting squats and social centres. Their core organising groups are normally made up of nice, likeable and admirable people. They provide spaces in which those who are excluded from mainstream society, for whatever reason, can experiment with different cultural norms and social orders that suit them and, from a moral point of view, it is difficult to find much to fault them on.

Meanwhile, the cultural gap between such communities and the general population, and the moral superiority and hostility that reinforces that gap, ensure that the possibility of contagion among the broader population is very limited. This possibility is further curtailed by the welfare state providing overwhelming competition in the provision of public services. Such communities rely heavily upon core groups of highly committed and idealistic organisers. They tend to pour a lot of energy into internal affairs and rarely persist longer than the commitment of the core group which established them. Rather than spreading ideas through contagion, they tend to construct significant cultural barriers between their own bohemian, youthful world and its values and the mainstream which surrounds them. This effectively inoculates the mass of the population against the spread of their political ideas. They become the ideas of a strange sub-culture to which most people do not belong.

It’s not just in theory that it doesn’t work. This counter-culture has not, in practice, spread. It has persisted in pockets around the industrialised world for half a century, but the pattern has resembled a few isolated flickers rather than anything resembling broad expansion. The European squatting movement probably peaked, in terms of numbers of people involved, in the 1980s. By the mid 1990's it was in decline, at least in Western Europe, a decline that continues to this day. The hostility to institutionalisation, along with the basic organisational problems, has meant that little legacy remains as the squats have closed and the cultural wind has changed.

Seriousness

The above text constitutes an analysis borne of many years experience. At the time when I switched allegiance from the counter cultural world to the far-left anarchists, I had a far less clear conception of what the problems were. In my mind, the contrast between the counter-cultural world that I had first been introduced to, and the far left anarchists of the Fédération Anarchiste (FA) was expressed by a single word: "serious". I had been used to a chaotic culture where most of the tedious work devolved on a small core of highly committed volunteers and there was a high tolerance of flakiness. This was, to my eye, a symptom of the political project not being serious. By contrast the “militants” of the FA, as they called themselves, were disciplined. They owned and managed bookshops and offices and had done so over decades. They had regular activities which involved the coordination of dozens of volunteers – distributing leaflets in the universities, attending demonstrations, plastering posters onto walls to advertise events, selling their newspaper. What really impressed me was their ability to marshal their membership to perform these tasks, despite the fact that they weren’t exactly good fun. In the anarchist counter-culture it was very easy to assemble a crowd for an activity that is considered fun, there is a drastic drop off when it comes to any activity that is not fun. By contrast, a large proportion of the militants of the FA showed up to such events – and they even showed up on time! These were serious people.

Towards the end of my stay in Lyon, I learned that, every week, the student branch of the FA would rise at 5 a.m. and travel to factories on the outskirts of the city in order to sell their newspaper to workers arriving to start their shifts at 7 a.m. This impressed me and appalled me in equal measure. Students rising at 5a.m. to sell newspapers outside factories - what a wonder! On the one hand, it was a truly impressive feat of voluntary collective action and self-sacrifice on the part of the members. These people were serious. On the other hand, it sounded like a thoroughly miserable duty to have to perform. But this was what serious political activists did, and I wanted to be a serious political activist. Gulp. If that’s what it takes…

By the time I left Lyon in May 1997, I was more firmly convinced of the merits of anarchism than ever, having witnessed anarchists operating on a new, larger scale. I had also turned decisively towards the political positions of the "serious" far-left, political anarchists and away from the counter-culture. Before leaving, I passed over the lease on my apartment to the Fédération Anarchiste and helped them turn it into an office - it became the editorial headquarters of their weekly newspaper. I was all set to take my freshly-fed political fire back home, to Ireland. But first a trip to work in the USA, into the belly of the beast, intervened.